Posted February 11, 2016

The cover story of the Marriott School of Management’s Alumni Magazine is a profile of the Neurosecurity Lab.

From the article:

Cerebral Security

Tech smarts and a pair of grants from Google and the National Science Foundation are helping BYU professors at the university’s Neurosecurity Lab lift the lid on computer users’ riskiest behaviors. And with a multimillion-dollar brain scanner at their fingertips, the six researchers are turning heads.

You can read the article here.

Posted February 11, 2016

We received our second Google Faculty Research Award for our proposal entitled, “Improving Adherence to Security Messages through Intelligent Timing: A Neurosecurity Study.” We were awarded $34,200, and Elisabeth Morant will serve as our Google liaison.

Our previous Google Faculty Research Award proposed to study habituation to security warnings.

From the Abstract:

System-generated notifications are ubiquitous in personal computing. Many of these interruptions are security messages that prompt the user to perform a security action, but these interruptions come at a high cost. Neuroscience has shown that the brain cannot perform even simple tasks simultaneously without significant performance loss, the result of a cognitive limitation known as dual-task interference (DTI). While some security messages require immediate attention, others can be timed to display when a user is best equipped to respond, i.e., when DTI is low. The goal of this proposal is to develop a system to predict low-DTI times using input-device tracking and mobile-device indicators of the user to display security messages at times when users’ adherence will be maximized.

Posted February 04, 2016

Update: The article is now officially published online here.

Our paper entitled, “How Users Perceive and Respond to Security Messages: A NeuroIS Research Agenda and Empirical Study,” was accepted for publication at the European Journal of Information Systems, a leading journal of the field of Information Systems. In our article, we lay out a research agenda for studying security messages using neurophysiological theories and methods.

The purpose of our research agenda is to demonstrate the promise of using neurophysiological measures, and encourage more research in this area. We believe that the approaches described in this article will provide new insights into users’ responses to security messages and facilitate more effective security message designs.

Why Use Neuroscience to Study Security Messages?

Research shows that users routinely disregard security messages. Although users may say that they are concerned about their security, their actual behavior doesn’t match what they say.

The theories and methods of neuroscience provide a promising lens to investigate the disconnect between what users say about security and actually do. The neural bases for human cognitive processes can offer new insights into the complex interaction between information processing and decision making, allowing researchers to open the‘black box’ of cognition by directly observing the brain.

Research Agenda

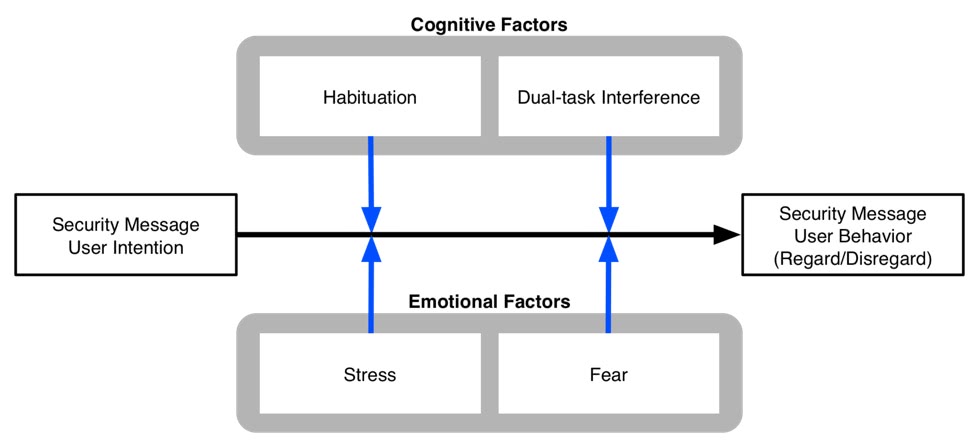

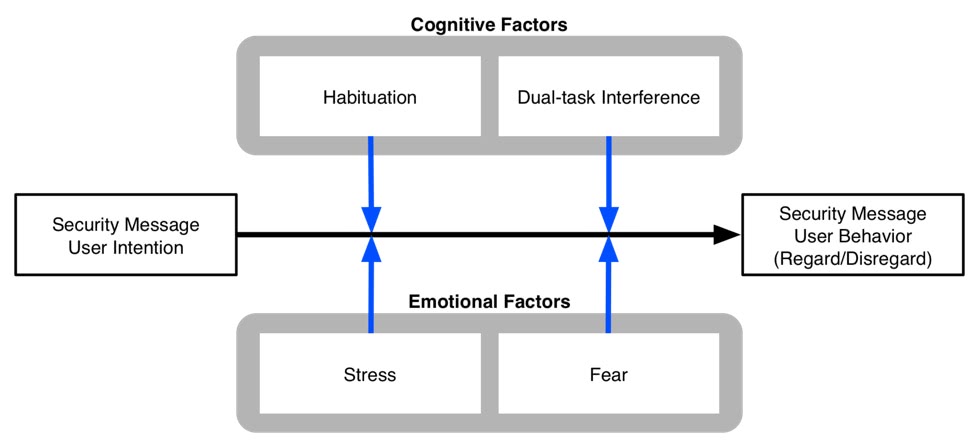

The figure above shows four factors that we argue interfere with users’ best intentions to comply with security messages: (1) habituation, (2) dual-task interference, (3) stress, and (4) fear. These are not the only important factors, but they are ones that we think the theories and methods of neuroscience have strong potential to address. We briefly describe each below.

How Does Habituation Affect Users’ Responses to Security Messages?

Habituation is the diminishing of attention because of frequent exposure to warnings. Through this process, warnings that were once salient become virtually unnoticeable, like familiar wallpaper. Habituation has been pointed to as a problem in many security-warning studies. However, it is difficult to observe using conventional methods because habituation is a mental state.

Neuroscience approaches can provide additional insight by directly measuring the mental process of habituation to determine (1) how quickly habituation develops in response to security messages, (2) how the neurological manifestation of habituation affects security behaviors, and (3) how long the effects of habituation on security messages persist. As an example, we’ve used fMRI and mouse cursor tracking to study habituation to warnings.

What Is the Impact of Stress on a User’s Response to Security Messages?

Recent research has highlighted the impact of‘technostress’, which is stress caused by interactions with information communication technologies. Stress can have profound detrimental effects on individuals’ productivity and well-being. D’Arcy et al (2014) showed that technostress has important implications for end-user security. An important gap in past stress-related security research is that survey measures capture a user’s perceptions of stress. perceptual measure of stress-inducing conditions, but nothing about the stress that someone is actually experiencing physiologically.

Two neurophysiological methods for measuring stress are cortisol-level measurement and skin conductance response (SCR). Cortisol (commonly called the stress hormone) can measure unconscious stress responses. When an individual’s stress level increases, so does the amount of cortisol in the body as psychological stressors stimulate its release into the bloodstream. Increases in cortisol can be measured easily with a saliva swab that is placed in a capsule for later chemical analysis (see image above).

SCR measures increases in the activity of sweat glands when an individual is stressed, and has been linked to measures of arousal, excitement, fear, etc. By using these and other methods, researchers can measure how users’ stress impacts their responses to security messages.

How Does Fear Influence Our Neural Processing of Security Messages?

Fear can have a powerful impact on how individuals respond to security messages. In information security, both protective and malicious messages commonly attempt to elicit fear to motivate the target into action. However, fear may invoke automatic responses that bypass cognition, leading an individual to not pay attention to a warning. As with stress, past research on fear has relied on survey measures, which don’t measure fear physiologically.

A variety of neurophysiological methods can be used to measure fear. fMRI can measure activation in areas of the brain associated with fear, such as the amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, and striatum. We propose that facial electromyography (fEMG) is a useful tool to detect fear in users interacting with security messages. With fEMG, visually imperceptible EMG activity in the muscle regions associated with facial expressions (over the brow–corrugator supercilia, eye–orbicularis oculi, and cheek–zygomatic major) can differentiate the intensity and valence of an individual’s reactions to visual stimuli.

How Does Dual-task Interference Disrupt Cognitive Processing of Security Messages?

Dual-task interference (DTI) is a cognitive limitation in which even simple tasks cannot be simultaneously performed without significant performance loss. Responses to security messages are susceptible to DTI because they are typically secondary tasks that interrupt the completion of a users’ primary task of using a computer. Unfortunately, when DTI occurs, performance is reduced for both the primary and secondary tasks, which means that users will not pay full attention to the security warning.

Brain imaging methodologies such as fMRI and electroencephalography (EEG) can be effective techniques for examining the cognitive consequences of DTI. Using EEG, the P300 brainwave component of the event-related potential can be examined, which is associated with attention and memory operations. The P300 reflects brain activity approximately 300–600 milliseconds after exposure to a stimulus. The speed of this measure reveals reaction differences in subjects before they have time to consciously contemplate a response. Monitoring a person’s EEG measures as they perform a computing task that a security message interrupts can allow researchers to see the degree to which the message disrupted the task and the level of cognitive resources devoted to the message. We used EEG in a past study to predict users’ responses to security warnings.

A Call for Research

Neurosecurity has the potential to provide new understanding of how users respond to security messages. We hope researchers will join us in researching the issues described above to significantly advance our understanding of security messages and how to design them to be more effective.

From the abstract:

Users are vital to the information security of organizations. In spite of technical safeguards, users make many critical security decisions. An example is users’ responses to security messages—discrete communication designed to persuade users to either impair or improve their security status. Research shows that although users are highly susceptible to malicious messages (e.g., phishing attacks), they are highly resistant to protective messages such as security warnings. Research is therefore needed to better understand how users perceive and respond to security messages.

In this article, we argue for the potential of NeuroIS—cognitive neuroscience applied to Information Systems—to shed new light on users’ reception of security messages in the areas of (1) habituation, (2) stress, (3) fear, and (4) dual-task interference. We present an illustrative study that shows the value of using NeuroIS to investigate one of our research questions. This example uses eye tracking to gain unique insight into how habituation occurs when people repeatedly view security messages, allowing us to design more effective security messages. Our results indicate that the eye movement-based memory (EMM) effect is a cause of habituation to security messages—phenomenon in which people unconsciously scrutinize stimuli that they have previously seen less than other stimuli. We show that after only a few exposures to a warning, this neurological aspect of habituation sets in rapidly, and continues with further repetitions.

We also created a polymorphic warning that continually updates its appearance and found that it is effective in substantially reducing the rate of habituation as measured by the EMM effect. Our research agenda and empirical example demonstrate the promise of using NeuroIS to gain novel insight into users’ responses to security messages that will encourage more secure user behaviors and facilitate more effective security message designs.

Article Download

Download a PDF of the article here.

Posted December 08, 2015

We have been awarded $58,185 by the NSF to supplement our grant, “The Force of Habit: Using fMRI to Explain Users’ Habituation” (CNS-1422831). The purpose of this supplement is to investigate how habituation (i.e., warning fatigue) to frequent pop-up notifications and warnings carries over or generalizes to warnings that a user hasn’t seen before.

From the supplement proposal:

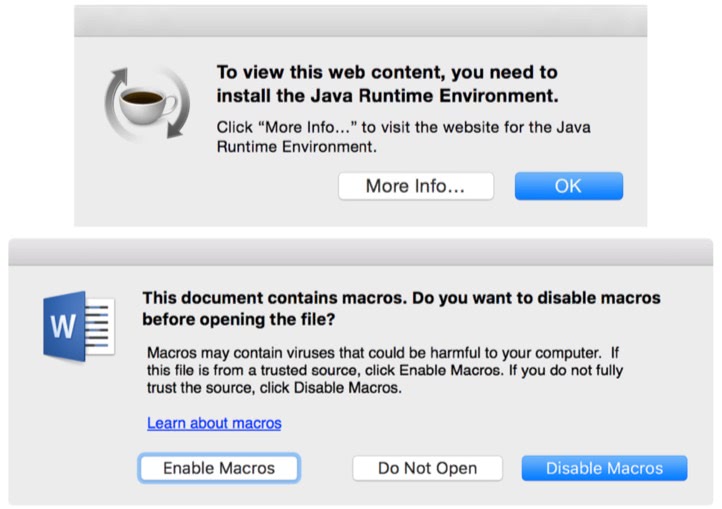

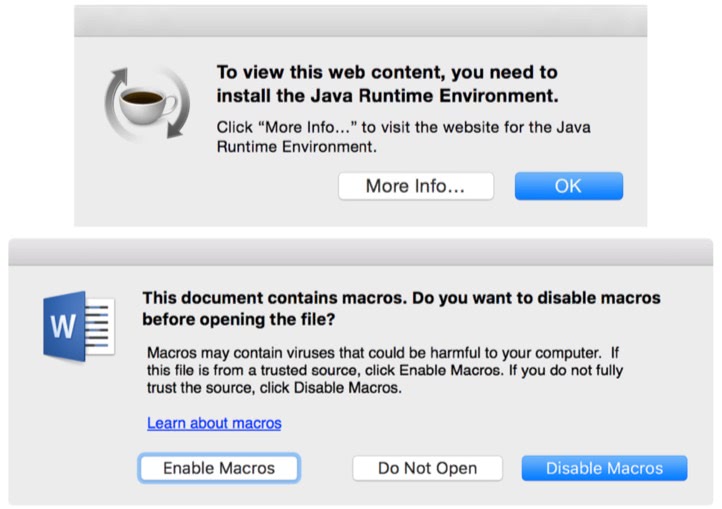

Generalization occurs when the effects of habituation to a repeated stimulus carry over to other novel stimuli that are similar in appearance. Applied to the domain of information security, generalization suggests that users not only habituate to individual security warnings, but also to whole classes of notifications and warnings that share a similar appearance and user interaction (UI) paradigm (see Figure 1). If true, then the threat and potential impact of habituation is much broader than previous work has suggested, as a user may already be deeply habituated to a security warning that he/she has never seen before.

Figure 1. A notification (top) and security warning (bottom). Note the similarities in UI and mode of interaction.

With this proposal, we seek supplemental funding to build upon the findings of our original grant to investigate this research avenue. We outline a series of complementary experiments using eye tracking and fMRI to (1) measure the extent to which the effects of habituation generalize across similar types of notifications and security warnings, and (2) determine warning designs that can reduce the occurrence of generalization.

With this supplement, the total NSF award is $352,526.

Posted September 28, 2015

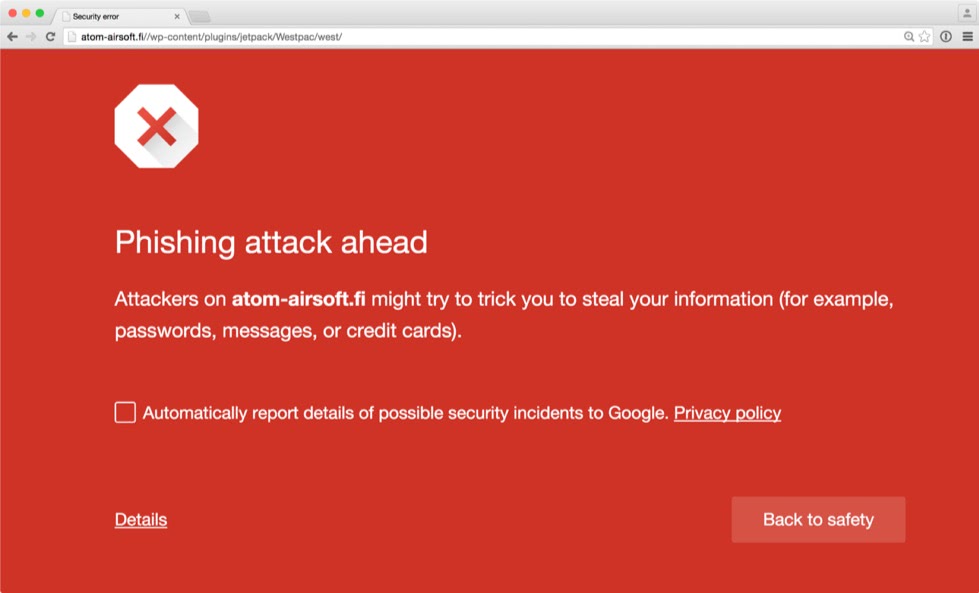

Our paper, “Neural Correlates of Gender Differences and Color in Distinguishing Security Warnings and Legitimate Websites: A Neurosecurity Study” has been accepted to the Journal of Cybersecurity, a new journal published by Oxford University Press. In this exploratory study, we used electroencephalography (EEG) to examine how two fundamental biological factors—gender and color perception—influence users’ reception of security warnings (see image of a BYU student participant below).

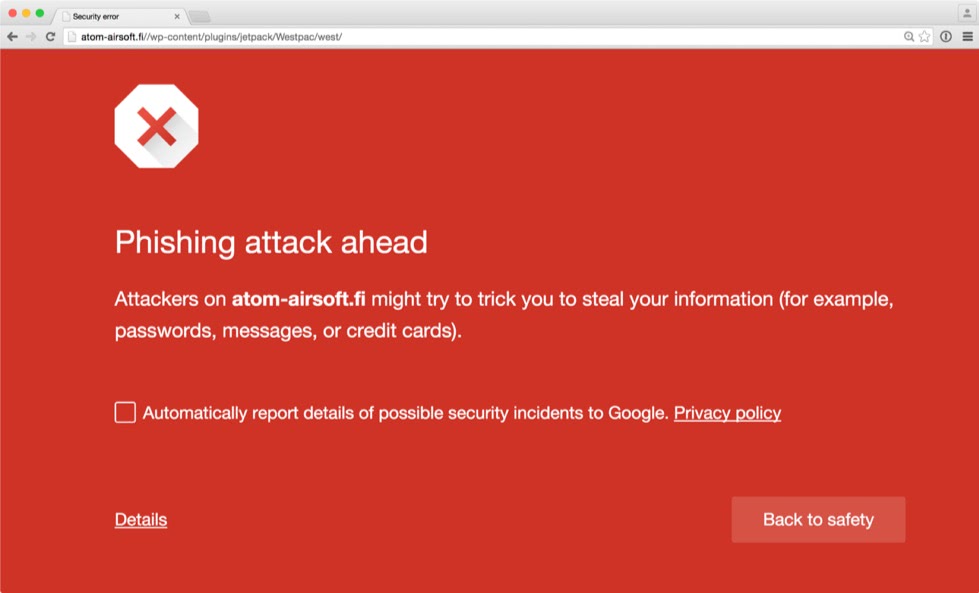

Our results showed that women exhibit higher brain activity than men when viewing malware warnings. However, we found that there was no change in brain activity when viewing red warnings (such as the Chrome phishing warning below) compared to grayscale warnings.

This paper is significant to our lab because it was the first neurosecurity study we conducted together. It also led to our expanded EEG study that was published last year in the Journal of the Association for Information Systems (JAIS).

From the abstract:

Users have long been recognized as the weakest link in security. Accordingly, researchers have applied knowledge from the fields of psychology and human–computer interaction to understand the security behaviors of users. However, many cognitive processes and responses are unconscious or obligatory and yet still have a profound effect on users’ security behaviors. With this in mind, researchers have begun to apply methods and theories of neuroscience to yield greater insights into the “black box” of user cognition. The goal of this approach—termed neurosecurity—is to better understand and improve users’ behaviors.

This study illustrates the potential for neurosecurity by investigating how two fundamental biological factors—gender and color perception—affect users’ reception of security warnings. This is important to determine because research has shown that users frequently fail to appropriately respond to security warnings. We conducted a laboratory experiment using electroencephalography (EEG), a proven method of measuring neurological activity in temporally sensitive tasks. We found that the amplitude of the P300—an event-related potential (ERP) component indicative of decision-making ability—was higher for all participants when viewing malware warning screenshots relative to legitimate website shots. Additionally, we found that the P300 was greater for women than for men, indicating that women exhibit higher brain activity than men when viewing malware warnings. However, we found that there was no change in the P300 when viewing red warnings compared to grayscale warnings. Together, our results demonstrate the value of applying neurosecurity methods to the domain of cybersecurity and point to several promising avenues for future research.

Article Download

Download a PDF of the article here.