The latest in our series of studies on habituation to security warnings, is now published in the June 2018 issue of MIS Quarterly, one of the premier journals of the field of information systems. This article, titled “Tuning Out Security Warnings: A Longitudinal Examination of Habituation Through fMRI, Eye Tracking, and Field Experiments,” is an expansion of our CHI 2017 paper that examined how people habituate to security warnings over the course of a workweek using eye tracking and fMRI. This paper includes that experiment, but we also conducted a three-week field experiment involving users’ warning adherence behavior on their personal mobile devices in order to test our lab findings in the field.

Eye Tracking and fMRI Experiment

Habituation is decreased response to repeated stimulation. In the context of security warnings, past work has shown that people “tune out” warnings after multiple exposures to them. However, previous studies on habituation (including our own work) only examined habituation during a lab experiment at a single point in time. This is an important limitation because habituation is a neurobiological phenomenon that develops over time. This means that past work has provided an incomplete picture of the problem.

To expand our understanding of habituation, we conducted a longitudinal experiment to see how habituation develops over the course of five daily experimental sessions involving 16 participants. In addition, we measured habituation using both fMRI and eye tracking simultaneously (Figure 1), which allowed us to measure habituation as it occurred in the brain as well as a behavioral manifestation of habituation (i.e., eye movements).

Figure 1. Our lab's EyeLink 1000 Plus long-range eye tracker mounted under the MRI viewing monitor.

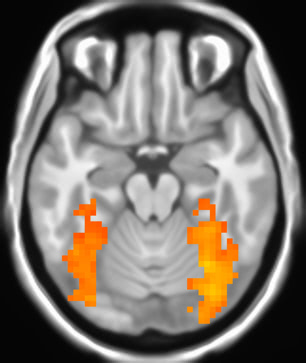

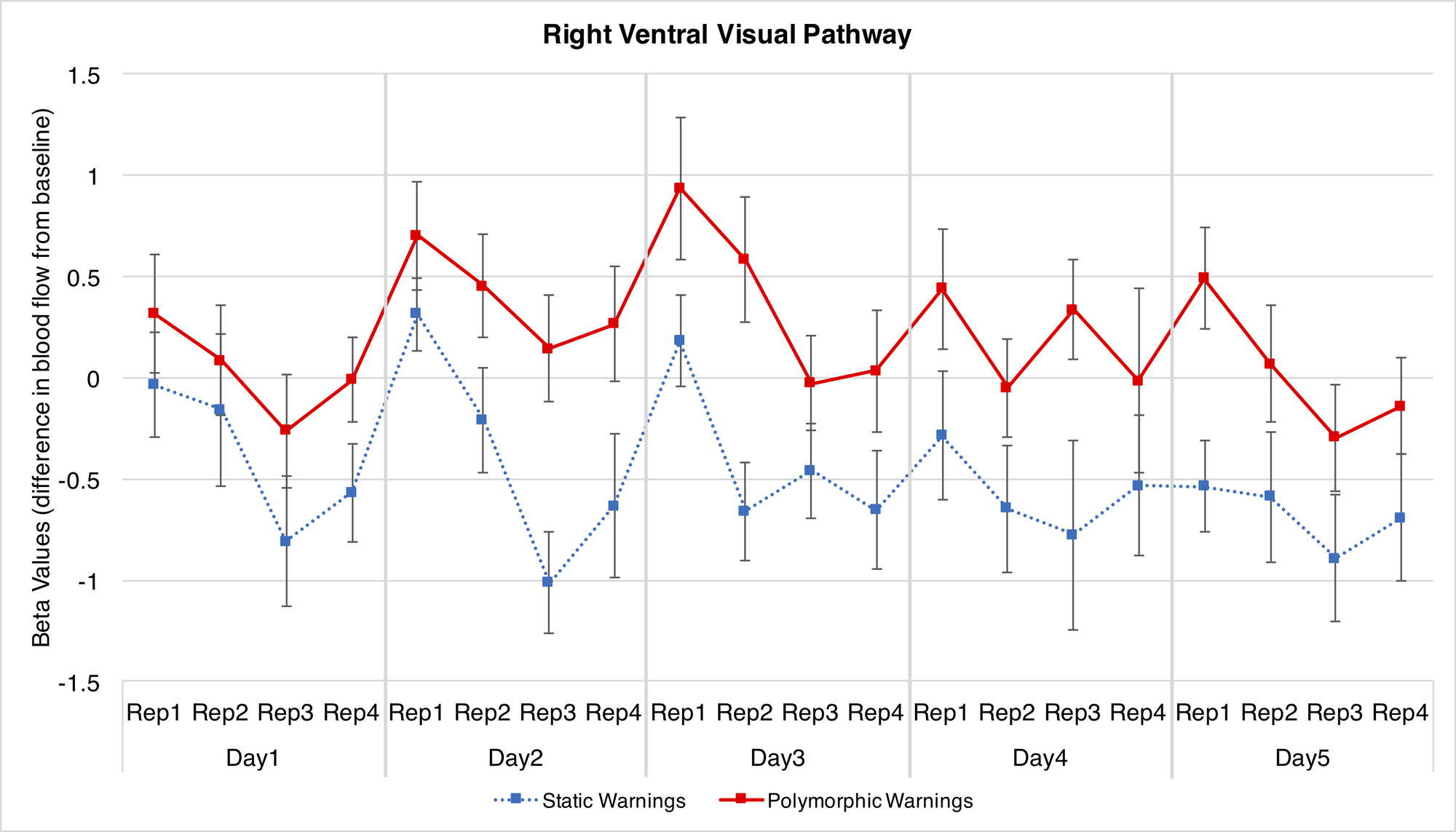

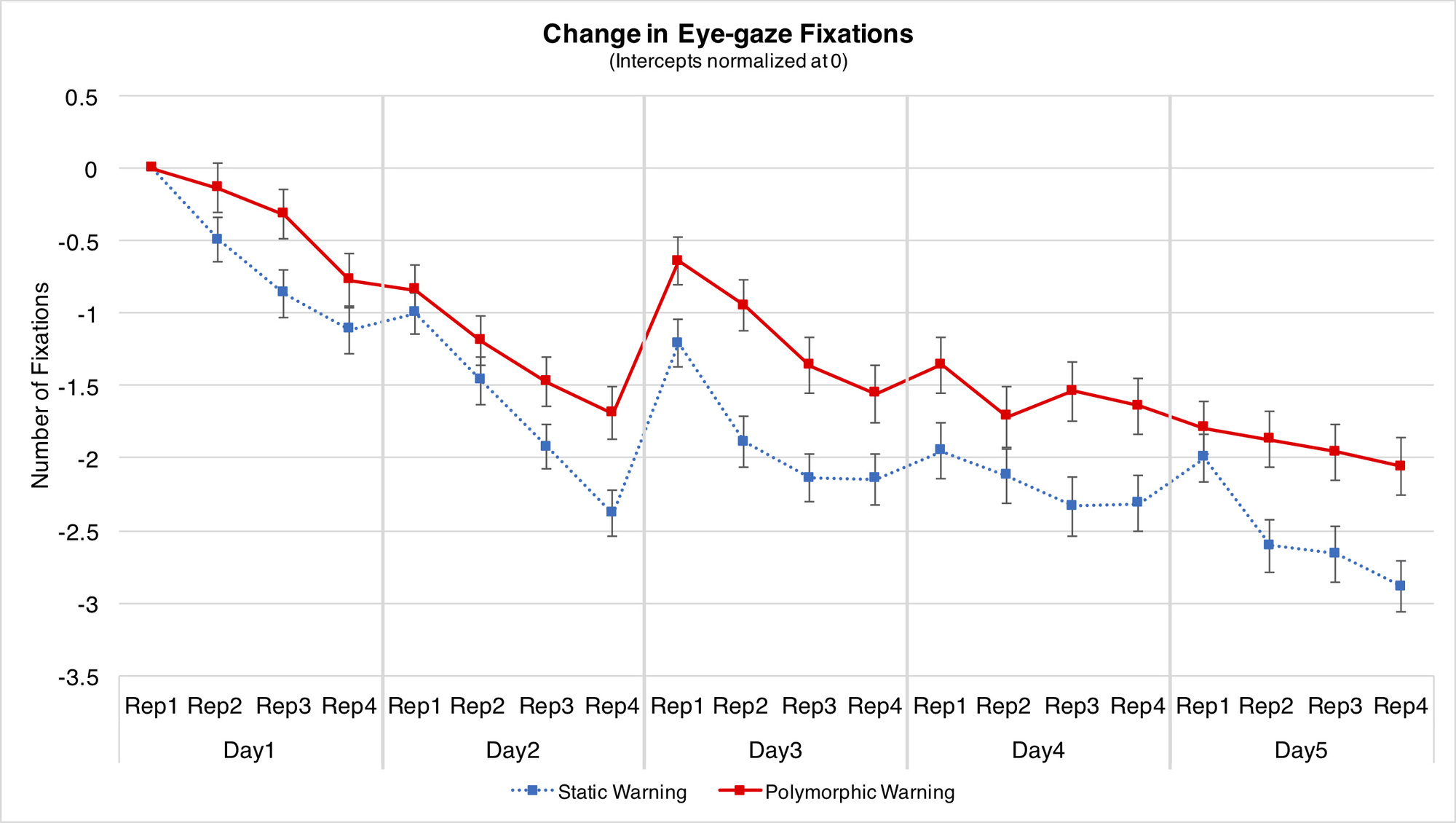

We found that people habituated rapidly to repeated warnings within a single laboratory session, both in terms of decreased neural activity (such as in the ventral visual pathways, Figure 2) and fewer eye fixations. However, we observed a recovery effect of attention from one day to the next when warnings were withheld. Unfortunately, this recovery effect wasn’t enough to offset the overall pattern of habituation across the workweek. This is depicted by the dotted blue line in Figures 3 and 4.

More positively, we found that a polymorphic warning, a warning that changes its appearance with each presentation, was able to significantly sustain attention over time. This is depicted by the solid red line in Figures 3 and 4. We found this result with only four variations to the warning.

Figure 2. Left and right ventral visual pathways.

Figure 3. Activity in the right ventral visual pathway in response to each presentation of static and polymorphic warnings.

Figure 4. Change in eye-gaze fixations across viewings.

Mobile Field Experiment

We also tested our lab findings in the field by conducting a three-week field experiment in which 140 Android users were naturally exposed to privacy permission warnings as they installed apps on their personal mobile devices. This had the benefit of improving the realism and ecological validity of the study overall, but it also allowed us see how habituation influences actual warning adherence behavior.

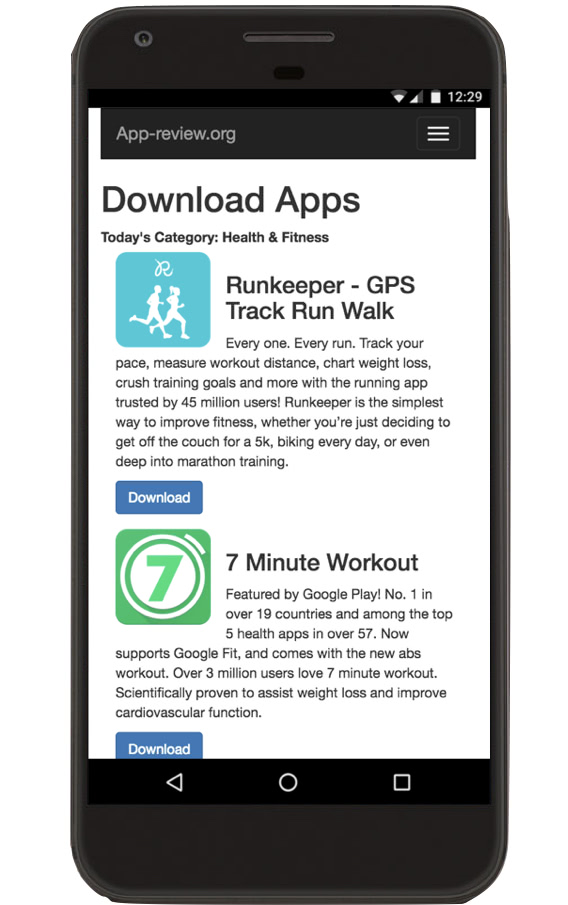

To do this, we designed an Android app store and required participants in the experiment to install three apps from a category of apps each day for 15 days (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A screenshot of the app store created for the field experiment.

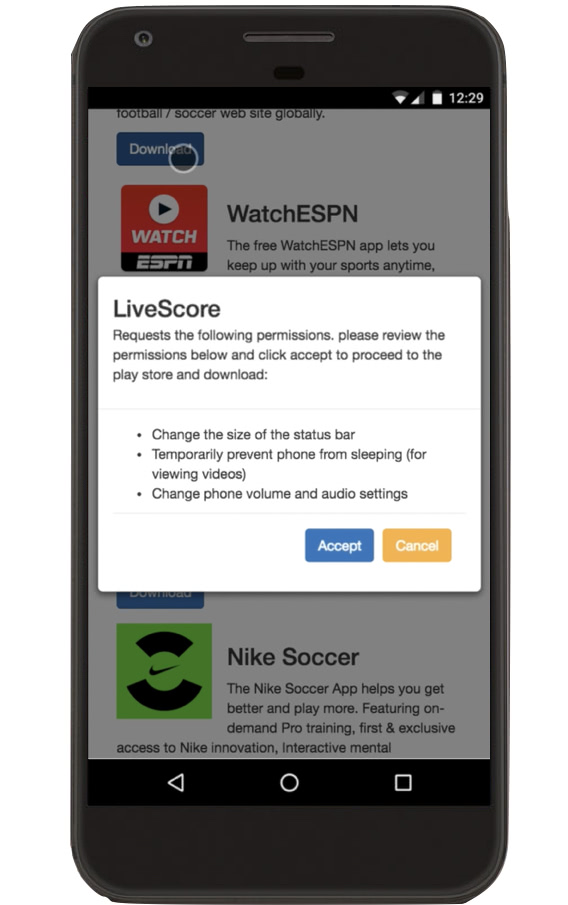

When participants selected an app to download, they saw a permission warning like the one in Figure 6. This warning listed permissions that the app requested to access or modify data.

Figure 6. A screenshot of the app store permission warning.

If a participant chose to install a warning with a risky permission, then this meant they disregarded the warning. To make this less subjective, we created four scary permissions that should be inappropriate for any app category:

- Charge purchases to your credit card

- Delete your photos

- Record microphone audio any time

- Sell your web-browsing data

If participants were paying attention, they should cancel the installation and find another app to install from the app category.

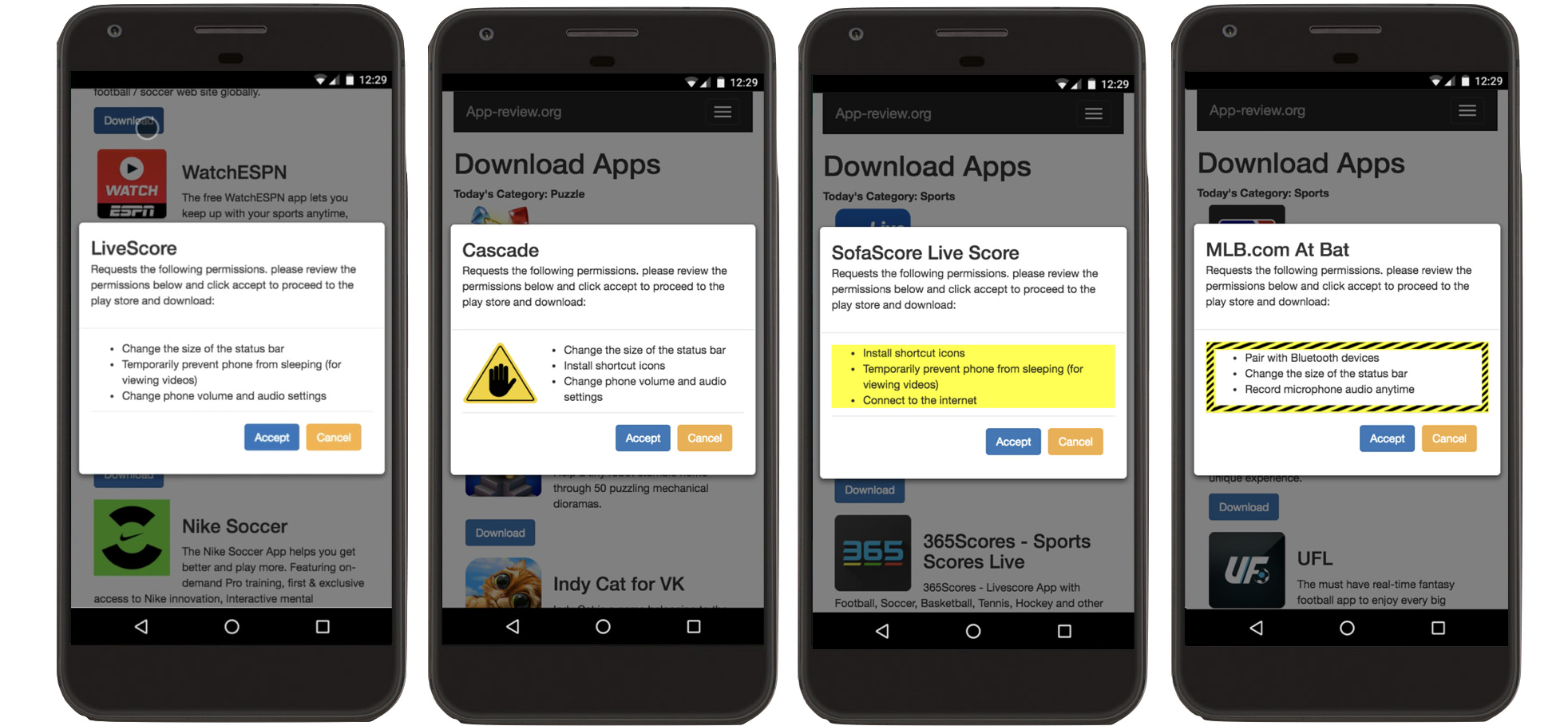

We then randomly assigned participants into one of two groups: a control group, that received the same warning every time, and a polymorphic warning that changed its appearance throughout the 15 days, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Sample polymorphic warnings.

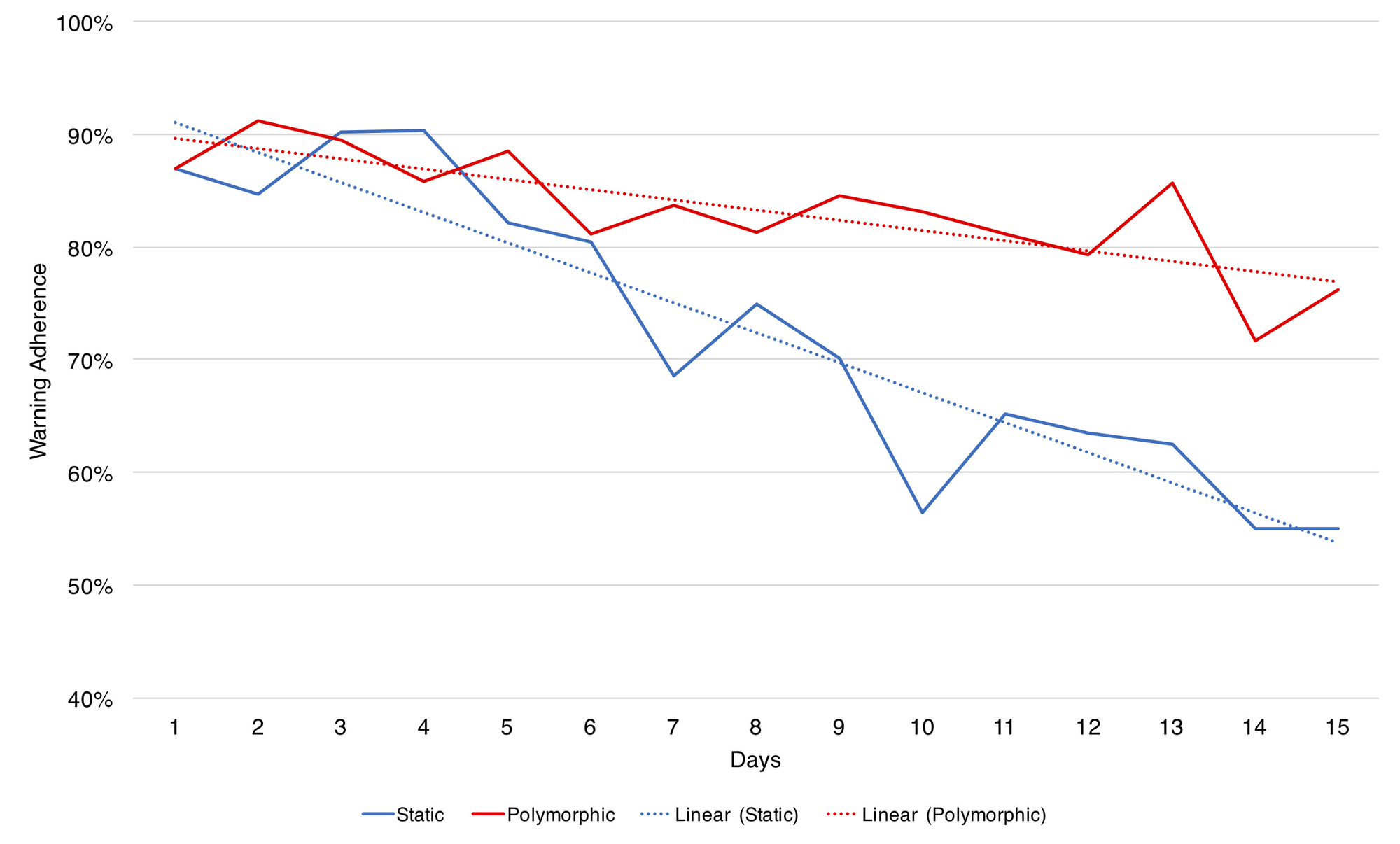

Consistent with our fMRI results, users’ warning adherence substantially decreased over the three weeks. Interestingly however, the average accuracy rate by the end for participants in the polymorphic condition was 76 percent, compared to 55 percent for participants in the static condition, a substantial difference (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Percentage of warning adherence in rejecting risky warnings across 15 weekdays for each treatment group.

What These Findings Mean

Together, these findings provide the most complete view yet of the problem of habituation to security warnings. First, they show that people not only habituate to warnings, but also that they recover from this habituation effect if a warning isn’t seen for a while (in our case, 24 hours). However, this recovery is not enough to compensate for frequent exposure to warnings over time. This means that systems designers need to be judicious in the number of times warnings are displayed to a user.

Second, we found that updating the appearance of a security warning can reduce habituation, as demonstrated by our eye tracking and fMRI data, as well as warning adherence behavior in the field. Even using a few variations can have a substantial effect over time. Although this study wasn’t the first to propose polymorphic warnings, it is the first to show that they remain effective over time.

Third, this study improves on past studies that were conducted in laboratories at a single point in time. The mobile field experiment showed for the first time how a realistic repetition of warnings in the field results in a decrease of warning adherence behavior.

From the Abstract:

Research in the fields of information systems and human-computer interaction has shown that habituation—decreased response to repeated stimulation—is a serious threat to the effectiveness of security warnings. Although habituation is a neurobiological phenomenon that develops over time, past studies have only examined this problem cross-sectionally. Further, past studies have not examined how habituation influences actual security warning adherence in the field. For these reasons, the full extent of the problem of habituation is unknown.

We address these gaps by conducting two complementary longitudinal experiments. First, we performed an experiment collecting fMRI and eye-tracking data simultaneously to directly measure habituation to security warnings as it develops in the brain over a five-day workweek. Our results show not only a general decline of participants’ attention to warnings over time but also that attention recovers at least partially between workdays without exposure to the warnings. Further, we found that updating the appearance of a warning—that is, a polymorphic design—substantially reduced habituation of attention.

Second, we performed a three-week field experiment in which users were naturally exposed to privacy permission warnings as they installed apps on their mobile devices. Consistent with our fMRI results, users’ warning adherence substantially decreased over the three weeks. However, for users who received polymorphic permission warnings, adherence dropped at a substantially lower rate and remained high after three weeks, compared to users who received standard warnings. Together, these findings provide the most complete view yet of the problem of habituation to security warnings and demonstrate that polymorphic warnings can substantially improve adherence.